our wartime overseas service began to

swing open. But the hinge was the testi-

mony, in that crucial moment, of a law-

yer who had found the Lord through

the Army's work with alcoholics!

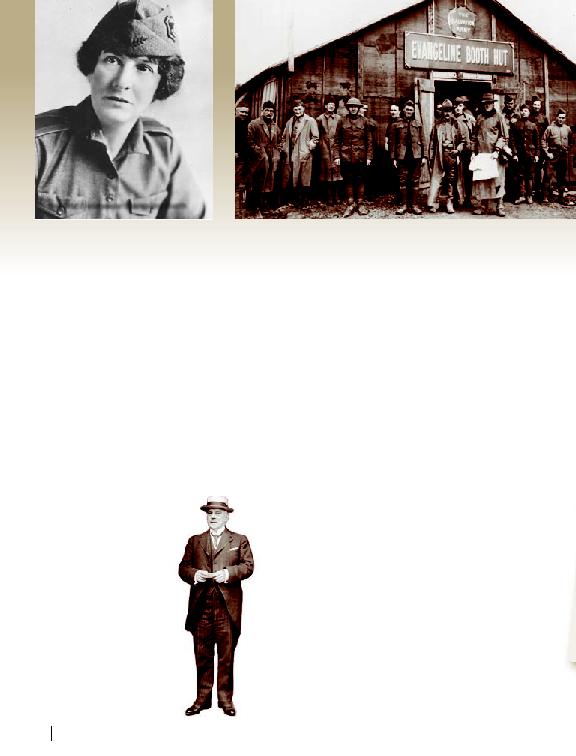

Salvation Army's work with American

doughboys overseas during World War

I, and the profound effect this had on

the public's perception of us. If so you

are likely to say, "That was a long, long

time ago. Why tell it again now?"

work, while carrying out his "normal"

ministry, was used by the Lord to do

something with unexpectedly far-reach-

ing results. The testimony of the lawyer

whose life was changed resulted in that

letter from the president's secretary.

It did not grant The Salvation Army

authority to put any specific plan into

motion, only the right to carry to U.S.

military leaders the offer to place

Salvationists at their disposal.

Armed with that letter and

sent to France, Colonel Barker

was able to deal directly with

American military officers. Some

of those brushed off the idea as ill-

advised, and had brushed him off

as well. But he pressed on until he

faced General John J. Pershing, a

man described by one historian as

"cold-eyed" and "granite-faced," a

consequence of the tragedy he had

and its aftermath now becomes a vital

part of our story.

REMEMBERS

completing a second tour of duty in the

Philippines, was living in San Francisco

with his wife and four children when

he was hurriedly called by President

Woodrow Wilson to halt the depreda-

tions of the elusive Mexican bandit,

Pancho Villa, who had the audacity to

make a surprise raid on a U.S. Army

cavalry garrison at Columbus, New

Mexico. Hardly had Pershing arrived in

El Paso, Texas, where his troops were

assembling, when he received tragic

news. His wife and three daughters

were burned to death in a fire in their

The Salvation Army's provincial

sympathy, as did other

titude was in sharp contrast

to that of the respectable

outsider. Often in those days,

brats" were not highly thought of in the

settled communities where they tem-

porarily resided. They would move in,

stay for a time, then suddenly move out

again at the behest of military leader-

ship. Pershing never forgot the Army's

kindness, which touched him deeply.

The renegade had not been caught,

although his bandits had ceased their

depredations. However, a more serious

problem had arisen; the government

of Mexico did not take kindly to having

American troops trespassing in their

country, even commandeering a loco-

motive for the pursuit of the bandit.

In fact, Mexico considered America's

intrusion to be an act of war. Finally,

President Woodrow Wilson decided

there were matters weightier than risk-

ing a full-blown war with our neighbor

to the south, so early in February 1917

Pershing, by then a major-general, and

his troops, were recalled.

picked by him, commanding an as�yet

non�existent expeditionary force. The

presidential directive was very specific,

stipulating that "the forces of the United

States are to be a separate and distinct

component of the combined forces, the

identity of which must be preserved...

you will exercise full discretion in de-

termining the manner of cooperation."

early stages. The French, British

The S

tit

to